The Glamour of Urban Decay

How Tony Manero and other leading men mythologized New York City's decline

There’s nothing quite like summertime in New York City. The air is heavy with the familiar fragrance of day-old curbside garbage and and subway pollution radiating from sidewalk grates. New Yorkers in business attire are yelling into their phones over a bad deal while profusely sweating through their several layers of tailored fabric. Even in a place as glittery as Manhattan, the heat and grime of the urban landscape melt the most statuesque and poised individuals among us into irritable puddles.

During one memorable summer, on a balmy walk just like the one I described, I was headed to Film at Lincoln Center to catch their latest retrospective: a 1970s New York City showcase of classic films. Everything from Saturday Night Fever to Pumping Iron was screening that week, and the series was essential viewing for anyone who loves New York-set movies, and the budding careers of 1970s and 1980s Hollywood stars.

After recently bemoaning the heat, and revisiting a few of my favorite films, I wanted to dig a bit deeper. As a culture, our fascination with New York City is timeless, but what is it about grimy 1970s Manhattan that people find so captivating and also incredibly relatable? For all the decrepit sidewalks, wet garbage, and pent-up frustration, derelict 1970s New York inspired some of the most affecting stories about a decade of fear - a decade that tapped into the primal emotions and reactions of people living in a society clearly in decline. A decade not too dissimilar from the one we’re living through now.

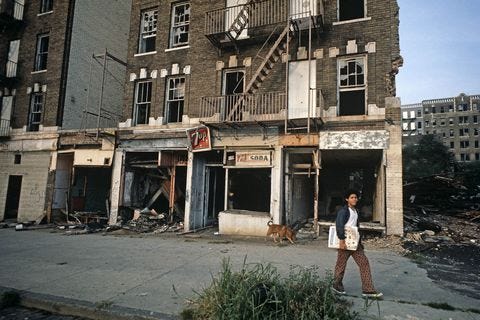

It felt it would be the perfect time to dive into this distinct moment in the city’s history. New York in the 1970s had a reputation of exasperation: it was an unsafe and unruly place. At the same time, no matter how dirty or decayed the aesthetic, New York was a destination for entertainment and the wealthy. The city became an icon of extremes: the insane excesses of celebrity and youth culture, and also of an impoverish urban wasteland. These contrasting visions brought New York major national attention as a morally bankrupt city of very few haves and thousands of have-nots.

The mid-to-late 1970s in New York City saw news headlines like the citywide Black Out in 1977, celebrity sightings at Studio 54, and the terrifying spree of the serial killer David Berkowitz better known as “Son of Sam”. Alongside this creative explosion and trove of tabloid wonders were a grueling recession, violent crime, and the rise of New York’s Master of the Universe icons such as Carl Icahn and Donald Trump. New York was simultaneously the most glamorous place to be, and the most disgusting, impoverished place at the same moment in history. Depending on the party you attended, or the neighborhood you lived in, the city’s identity was a parallax.

A financial recession hindered the United States in the mid-to-late 1970s, and the impact in New York City was substantial. There had already been a shift from urban living to the suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s, and existing trends further escalated as high levels of violent crime led to a major population loss. By the end of the 1970s, nearly a million people fled the city, or a nearly 10% loss in population, which dramatically impacted civic life. With fewer people, municipal tax revenue declined, and a highly unionized, public sector workforce, saw their economic prospects crumble. All of these factors stoked existing divisions in the culture. People had to fight for fewer resources and opportunities.

At this point in mainstream Hollywood, the era of The Godfather and moody prestige films like Chinatown was in full swing. The movies at the box office tapped in the depressing mood across the country, but their sanctimonious nature began to tire audiences. Studio films were becoming too cerebral, and not tackling the crude outrage the average American was feeling. That changed when the character of Paul Kersey, armed vigilante and older leading man of Death Wish (1974) debuted. Aggrieved audiences had their new icon in the over-the-top violent, revenge fantasy in a crime-infested exaggerated New York City.

Death Wish debuted on the heels of the financial recession of 1973-1975 and the oil embargo of 1973. The film stars Hollywood legend Charles Bronson as Paul Kersey, a successful architect who lives in New York City with his wife, Joanna. One day, while Paul’s adult daughter, Carol, is visiting, muggers follow Joanna and Carol home from D ’Agostino’s grocery store and violently attack them. Joanna dies in the hospital from her injuries, and Carol is essentially catatonic from PTSD a gets committed to a mental institution. Devastated by the incident, Paul is overcome by despair from the violent incident he was absent for. After a colleague gives him a gun a few weeks later, Paul begins to experiment with killing muggers and street criminals in a twisted form of vigilantism. Paul lures petty thieves and criminals into traps so he can kill them, and his erratic behavior continues to spiral. When the NYPD take notice of the killings, they aren’t sure how to act because Paul’s brutal assault on random criminals has drastically decreased the crime rate. It really is a morally bankrupt city, huh?

What’s so remarkable about Death Wish, and the various sequels it spawned, is how the population identified with Paul and essentially revived the career of an aging Charles Bronson. The movie star became the Bruce Willis of his day, and became a hero to the next generation. The critics were never fans of Death Wish and its sequels, due to its exploitative violence and moral ambiguity, but audiences were obsessed with Paul Kersey’s urban rampage. Some would even stand up and cheer in theaters when he murdered his next victim. At the time, violent crime skyrocketed across The United States, so perhaps seeing an aggrieved man, who was angry with the world, shooting nameless muggers and perceived criminals, felt cathartic. Death Wish targeted and spoke to the same people who participate in contemporary Rage Rooms. It didn't seem fair that the country was going to hell in a handbasket. A fifty-something white man like Charles Bronson appealed to a certain subset of Americans that felt “left behind.” Pair those emotions with exploitative violence, and you have a hit movie.

A more ambivalent younger generation had their own heroes. In the 1970s, baby boomers in their 20s and 30s worked out their anxieties on the dance floor, embracing sexual liberation and the buoyant beats of the disco era.

When Saturday Night Fever (1978) arrived, the timing of its debut was perfection. The sensation captured the disco era just as it began to peak. The wildly popular film became famous for its killer Bee Gees-composed soundtrack, a fly-on-the-wall look at disco fashion and culture, and for making John Travolta and full-fledged movie star.

The film is based on the 1976 New York Magazine essay Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night, a gorgeously written tale of a nightclub in Brooklyn and the tight-knit group of male friends in their late teens and early 20s who frequent it. John Travolta’s guileless Tony Manero wanders through life, with dreams to win a local dance contest and be the hottest, most tantalizing man at Bay Ridge’s 2001 Odyssey.

The movie and the article are both exercises in observation and ambiguity, with a voyeuristic touch guiding the viewer through a shallow jaunt to find the meaning of life… or at least, what the meaning of life is for a 20-year-old Italian-American male who loves women and never left his neighborhood. While several baby boomers went away to college, a large portion of them stayed behind, and most moved back home with their parents after school. Baby boomers had different values. They were more liberal, consumerist, and sexually free, and in the face of a recession and socio-economic challenges, here they were living with the older generation who were more traditional and did not understand. It was tough to be a young person in the 1970s, and the best coping mechanism was indulgence no matter how trivial.

By the end of the decade, violence, crime, and economic anxiety were mainstays in popular culture with a sour mood of resentment simmering throughout the entire United States. Popular opinion was becoming more reactionary and less progressive, These feelings of economic anxiety and fear were palpable across the United States, with high crime, teenage runaways and underfunded schools. Films like The Warriors (1979) and Cruising (1980) fanned the flames of the conservative agenda and gave people an excuse for their disdain and outrage further exploiting New York’s image.

Warriors features the titular, fictional gang in a post-apocalyptic New York City. They are called for a summit in The Bronx with all the other gangs in the city for a resolution to bring every criminal group band together to create one ruling party for mob rule over the city since their members outnumber the police. However, it is revealed that a member of The Warriors gang is accused of killing another gang’s leader, and now all the other gangs in the city turn on them in full force. They are out to kill The Warriors, and the gang must race back through the decay of the city to their home base in Coney Island.

The cult classic features disaffected young men who have no choice but to join a gang in derelict New York City, that while fictionalized, doesn’t differ much from the city’s 1979 graffiti-tinged landscape. Street gang culture in The Bronx neighborhood of New York City flourished throughout the 1970s. The city cut back social services such as childcare, community centers, and municipal jobs. Since the fire department budget was drastically cut, and the city on the verge of bankruptcy, there were no personnel to police streets, put out fires, or provide care for children. Arson by gangs, cuts to the FDNY, and lack of building maintenance created a regular cycle of buildings on fire in the city’s poorest neighborhoods. Burned out buildings and scarred relics of formerly vibrant blocks dotted a landscape growing more apocalyptic. Between 1970 and 1980 The Bronx lost more than 97 percent of its buildings to fire and abandonment. This bleak landscape and lack of public places for kids to go created a vacuum, and gangs took advantage by recruiting young people and controlling the streets.

The Warriors tapped into the anger and the helplessness felt in communities like The Bronx. It was popular with younger audiences, and gang members in particular. Some gang-affiliated individuals attended early screenings of The Warriors leading to violent outbursts where people were stabbed or killed. This led Paramount to pull the film’s marketing and seek an alternative route for release.

In a similar vein, Cruising also instilled the same resentments and created animosity with its release, but in a much different way.

The Al Pacino-led film features a rookie cop going undercover into the Leather Bar community in New York City to solve a string of murders where the victims are gay men and affiliated with the BDSM scene. The movie was shot in New York's most notorious Leather Bars, and real-life patrons acted as extras. Beyond this inclusion, the movie is far from authentic and at times problematic. Al Pacino’s character is visually uncomfortable and frustrated for the entirety of the movie, and the way the bar scenes show the community feels too exhibitionist.

Conservatives hated the idea of Michael Corleone in this queer-adjacent role dancing in a Leather Bar, and the LGBTQ+ community protested during the shooting of the film and during its release due to its treatment of gay characters and themes. There was anger on both sides of the spectrum, and the movie was the embodiment of popular culture’s polarizing themes. Cruising was more along the lines of Death Wish in the critical response - it was almost too ambiguous for people to accept it, and the gay community was appalled at the lack of empathy and spectacle is created.

However, Cruising’s depiction of NYC’s sexually explicit underbelly is a time capsule of the LGBTQ+ community before the AIDS crisis. It also mixes the anxiety of the era with sexual liberation, violent crime, and the evolution of urban areas into adult play lands in all their raw glory. In recent years it’s been re-assessed by queer cultural critics and other audiences, and I think its polarizing quality is why it’s emblematic of the late 1970s image of New York City.

The movies of this time all feature the same hardcore imagery and ambiguity - regardless if it's Tony Manero dancing on a Saturday Night, a cop perusing a leather bar, or a fifty-something man going on a violent rampage, the despair and disappointment about a better tomorrow radiated in every American. The future looked bleak if this is where the culture was headed.

Today’s New York looks extremely different than the wasteland depicted in movies of the 1970s. The feelings of frustration and economic anxieties are still very much alive and well. Just walk down 7th Avenue outside of Penn Station and you can feel the resentment boiling over in people trying to make their way through a menagerie of colorful characters and street urchins.

If you see a man in full formal dress on a hot day, shouting into his cell phone about a deal that didn’t happen, he’s might be channeling some other sort of angry Al Pacino or Charles Bronson fantasy in his head.

When that deliciously grotesque combination of heat and pollution butts up against the egos and opinions of New Yorkers, there’s bound to be an outburst somewhere.

For Further Enjoyment-

Top Tracks:

Photos of New York in the 1970s

NY '77: The Coolest Year in Hell (Vh1 Documentary)

On my first visit to NYC, fresh out of a Gypsy Cab with a huge Nigerian driver out of Newark at midnight, in 1990 was being given a map off the area with one colour shading of don't go anywhere here at all, and another of don't go to any of these locations after dark. No cab will come and get you. Of course those places included venues like The Cotton Club that I so wanted to go to!