Beverly Johnson is one of the most beautiful women I’ve ever seen photographed. She possesses a duality of gentle femininity and bold confidence that reminds me of Jackie Kennedy. Like Jackie, Johnson has a gentle command and refined poise that makes you think of The House of Windsor or the Miss America Pageant.

In the photo above, Johnson wears a gorgeous ensemble of creamy wool, silk, and luxurious fur, and illuminated by natural light. She has the glamour and gumption of a young ingenue from a 1940s Hollywood movie, but also appears distinguished and worldly, even at age 21. Beverly Johnson’s whole vibe is the same as a 1990s vintage Ralph Lauren ad: aspirational Americana.

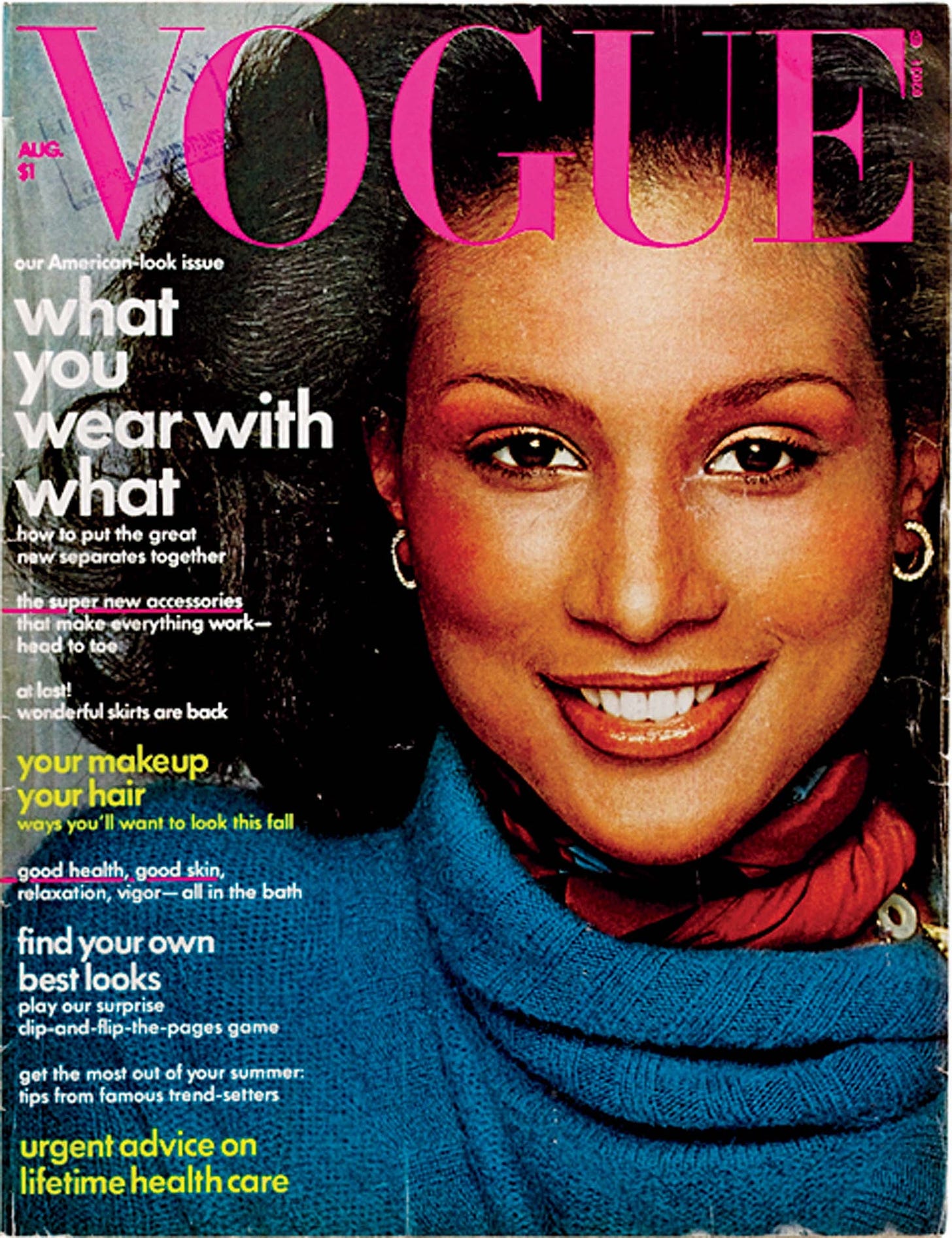

This photograph of Johnson is from one of the most famous Vogue issues in fashion history: August 1974. That issue was not Johnson’s first appearance in Vogue, but it was her first cover, and more notably, it was also the first time Vogue published a magazine with a Black woman on the cover. Johnson’s inclusion set the stage for what would become a new era of Black representation in fashion and popular culture. It was also part of a sisyphean struggle for inclusion we’re still fighting today.

I want to begin by saying that while Beverly Johnson’s Vogue cover was monumental, Black models had been photographed for major fashion magazines throughout the 20th century. However, the very white, very male mid-century fashion industry was slow-moving and highly exclusionary (I mean… it still is today.) Most European and American designers and magazines favored “white-passing” models, and while Donyale Luna and Naomi Sims paved the way for future supermodels, their successes were often stunted by the racism of mainstream fashion institutions.

Pat Cleveland, one of the most famous fashion models of the 1970s and notable “Halstonette” was actually featured in Vogue as early as 1970. She was a notable talent, but often passed over or excluded from mainstream publications. In 1971, after experiencing several years of racist attitudes and hostility from the industry she grew disillusioned by American fashion and moved to Paris. She proclaimed that she wouldn’t move back to the United States until a Black woman was featured on the cover of Vogue magazine. Three years later, Cleveland saw her demand realized in Beverly Johnson’s landmark cover.

So who is Beverly Johnson beyond this moment? How did she become this beacon of Black representation in the mid-1970s?

Beverly Johnson was born and raised in an upper-middle-class family in Buffalo, New York, and graduated from high school in 1969. During the early 1970s, and at age 19, she tried her hand at modeling and interviewed at several notable Madison Avenue agencies to attain representation. She was turned down by almost all, but when she interviewed at Glamour magazine, Johnson was hired on the spot. Her first cover for Glamour was in 1971 and it became Johnson’s big break. She set records for magazine sales, and Johnson appeared on the cover of Glamour six more times over the next few years. I hope those modeling agencies who originally rejected Johnson really felt the anguish in seeing those issues of Glamour.

In 1973, Beverly Johnson caught the attention of Vogue magazine and she did some photoshoots for them. At the time, Vogue’s sensibility was safe and extremely white (and some would argue is still that way today.) Johnson actually tested for Vogue’s cover multiple times before being chosen when another model was bumped. In August 1974, she appeared on the below cover, with the same approachable confidence and poise that became her signature:

The August 1974 issue was wildly popular, and also produced record sales. Beverly’s mainstream appeal and First Lady elegance resonated with readers across the spectrum of U.S. culture. She even returned to the cover of Vogue next year in 1975 for their “American Woman” issue, her status as fashion icon further cemented.

At this point, Johnson was a household name, and her success appeared limitless. Part of the reason Beverly Johnson was so well-received at the time was due to her approachable image. Much like other Black celebrities who were the “first” in their profession, Johnson’s image was exceptionally idealistic and polished. It is also clear in the interviews I read, that Vogue chose a Black woman who would be palatable to white audiences.

This doesn’t take away from the fact that Johnson was talented and fashion fans from all backgrounds adored her photos. She often had to fight for recognition, and continue to prove herself, even after achieving tremendous financial success. Her mood at this time can be felt in her 1975 NYT profile “I’m the biggest model, period.”

Beverly recently appeared on Jack O'Brian's radio show. “You're the biggest black model in the business,” O'Brian said.

“No, I'm not,” Beverly said. “I'm the biggest model—period.” She elaborates: “I've been in the business four years. There's not a model, black or white, who's done what I've done in such a short time.”

Johnson has stated in recent years that she was paid far less than her non-Black peers, and had to intensely advocate for herself when it came to business decisions. Even though photographers loved her, Beverly Johnson was seen as difficult for asking for Black hairstylists or make-up professionals during shoots, requests that were almost never granted.

While more Black models were being used in campaigns, the amount of racism and exploitation in the industry remained rampant. Models like Iman and Grace Jones entered the scene in the mid-to-late 1970s, and equity in fashion and inclusion was anemic. The next time a Black model appeared on the cover of Vogue it was in 1977, and the following appearance wasn’t until the mid-1980s. Grace Jones stated in her memoir that Johnson’s dominance in the American fashion industry inspired Jones to mainly work in Europe due to a lack of jobs. The financial piece of the pie was extremely small for Black models, and Jones ended up following in Pat Cleveland’s footsteps.

Beverly Johnson pivoted into acting, eventually starring in the poorly reviewed 1979 film Ashanti starring Michael Caine and Omar Sharif. Her acting and modelling career stalled and she guested on a few television shows in the 1980s. However, she kept her signature confidence and approachable nature and worked in media and fashion throughout her adult life.

One of the most horrific moments in Johnson’s career was revealed in her 2014 Vanity Fair essay; she auditioned for an episode of The Cosby Show in the early 1980s and was drugged by Bill Cosby after meeting him at his New York home. Johnson’s story was one of the flashbulb moments that catalyzed the movement towards holding Cosby’s predatory behavior accountable.

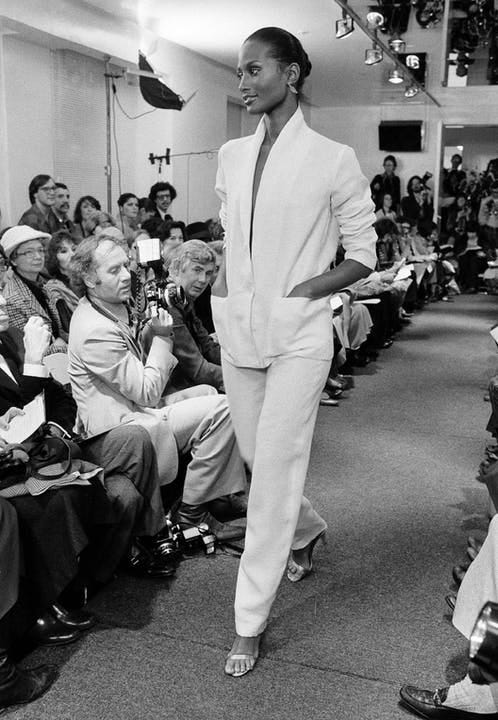

Now firmly in her elder stateswoman role in the fashion community, Beverly Johnson continues to model in shows, and advocate for change in the industry. She wrote an op-ed a few years back calling out Vogue, Anna Wintour, and fashion houses Gucci and Burberry for their racially-insensitive designs. She continues to possess her First Lady-style elegance, and glowing aura in all the interviews I’ve watched. It’s hard to keep your eyes off her, and she turns 70 this year!

Beverly Johnson wasn’t the only prominent Black model in the 1970s, and I’m sure there will be more stories to come about her peers. We’re thankful she’s still walking in shows and advocating for change.

For Further Enjoyment-

Top Tracks:

VIDEO: Beverly Johnson closes a diverse Bibhu Mohapatra runway show at NYFW

I'm the biggest model, period (NYT 1975 Profile on Beverly Johnson)

B-Sides:

Vanity Fair Story by Beverly Johnson: Bill Cosby Drugged Me

Vogue: How Beverly Johnson Broke Fashion's Glass Ceiling