Garfield, Cathy, and the malaise of our modern world

How late 1970s comics conveyed a generation's disillusionment and predicted the rise of consumerism

I know this is a bit of a hyperbolic statement, but I think that Garfield the cat is one of the greatest influencers in modern society. Yes, I know he’s a fictional character and also…. a cat. However, when Garfield was created in 1978, he became a generational icon of instant gratification and cynicism towards our society. Garfield is a member of the leisure class in every way: he's a consumer, and always annoyed by some banal aspect of his highly privileged life, and lazy. This orange cat who adores food and hates Mondays? He perfectly captures the feeling of late 1970s malaise, the rise of consumerism and instant gratification, and people love him.

This week we’re going to take a jump forward from the radical changes of 1973, to the monotonous malaise of the late seventies.

What happened when Boomers graduated from college, had children, and became contributing members of society? Was everything as idealistic and filled with sunshine and spiritual freedom as earlier years promised? Spoiler Alert: it wasn’t.

The 1960s and 1970s were revolutionary for the sheer speed of society’s embrace of movements such as Women’s Liberation, Black Power, The Environmental Movement, Gay Liberation, and others. All this activism and visibility gave people hope for a more inclusive, fairer country, and the hard conversations and political battles ultimately impacted the laws and culture of the United States. These glimpses of utopia inside The Human Potential Movement gave people the false promise that conditions in society and the self would continually improve.

By the late 1970s, the political and societal might for social and environmental justice began to fizzle. All the self-searching introspection of the Human Potential Movement devolved into what several thought-leaders called “society’s growing narcissism problem,” During the Carter Administration, social justice effectively took a back seat to economic and geopolitical issues. President Jimmy Carter was elected in 1976 as a progressive candidate for change. He was an outsider, civil rights supporter, and advocate for an America that embraced the hard truths of life. During Carter’s short tenure in office, his tone was one of austerity and sacrifice. Notably, in a televised address in 1979, he speaks of his vision of America:

“We have learned that ‘more’ is not necessarily ‘better,’ that even our great nation has its recognized limits, and that we can neither answer all questions nor solve all problems … we must simply do our best.”

During the mid-1970s and throughout the Carter Administration, there was economic turmoil and record-setting violent crime. Seemingly ack-to-back economic recessions with the stock market crash in 1974-1975 and again in 1979. People grew distrustful of society; the more chaotic and disrupted their lives became, the more people wished for affluence and security through any means necessary. People were frustrated and looked to the little comforts of consumer products, fashion, and food to find solace. The economics of this time also disrupted the ambitions of baby boomers graduating from college. People became risk-averse and sought professions that could provide income security, even if it meant sacrificing creatively and socially fulfilling ambition.

Additionally, there was a trend of people moving away from big cities due to fears about violent crime. This anxiety over safety was pervasive and signaled a more reactionary mood where society retreated from its 1960s openness and grew into a siloed, self-centered world.

Even though President Carter was a Democrat, society was still fairly conservative, and these new ideas inclusion were not well-received or at least misunderstood by the majority. Women and the LGBTQ+ population may have received landmark freedoms and increased visibility, but popular opinion was still very hostile towards them. After a while, the pendulum began to swing back hard. This discomfort with social change paired with a desire for security was a major reckoning for the generation that appeared to value inclusion and a utopian, communal ethos above all else— times really had changed.

In 1976, in the same month that Jimmy Carter was elected president, a new character was about to enter the zeitgeist. She would embody this confused, anxious society, and the generation of boomers that was reeling from it all: Cathy Guisewite and her synonymous Cathy comic strip.

Cathy debuted as a daily strip in late 1976 and was inspired by Guisewite's own trials and tribulations as an unmarried, quasi-feminist, working woman. Cathy's experiences capture every kind of prototypical personal crisis a woman encounters in the modern age including body image issues, dating woes, sexual harassment, political identity, and her place in an ever-evolving world that is hostile to women.

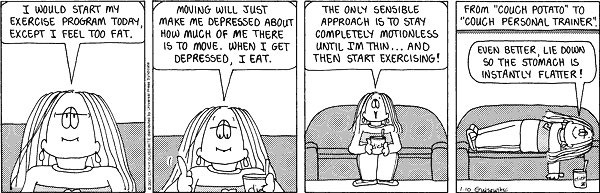

At first, Cathy was in circulation at a few dozen major newspapers across the United States, but her success rapidly rose in the 1980s and hit a peak in the 1990s. Guisewite and her Cathy character became the voice of the boomer generation in the same way Lena Dunham was in the 2010s for a certain type of millennial woman. And like Lena Dunham, people admired Cathy for her searing commentary and uncomfortably on-the-nose portrayal of a woman bemoaning society’s expectations of her, while also at the same time, very much maligned and hated for those same things. Cathy complained about her life and centered herself as a victim constantly. The most prolific of all the gripes Cathy shared via the comic strip, were ones about her weight and self-esteem.

The 1980s is often credited as the era when fitness and health boomed globally, yet the majority of the products and techniques amassed by a generation of dieters really took hold in the decade before. While Women’s Liberation may have championed equality for women, it didn’t thoroughly address the inequities tied to beauty, body image, or other sexist elements of consumerism. A lot of feminists or appreciators of Women’s Lib still very much desired the “perfect” body and validation from men, almost as if they were currency. This self-commodification was confusing, and women were attempting to forge an identity alongside a laundry list of tasks including having a career, choosing to have children, finding a husband, and gaining equity. The pressure to look thin, feminine, and be successful dieting was another ball the modern woman needed to juggle, and quick fixes were available in droves.

This era of consumerism was marked by instant gratification, and liquid diets emanated this so clearly. In 1976, Slim-Fast debuted on the market as a form of liquid diet. It was a form of crash dieting, meant to induce weight loss extremely quickly, even if you were starving yourself on 400-calories per day of a mystery concoction. The most notable of these liquid diets was called The Last Chance Diet. The 400-calories per day diet consisted of a 'Prolinn drink' made from slaughterhouse leftover products with very little nutritional benefit. People began to develop heart arrhythmia and 60 people died within the first few years of the diet's debut.

Another creation during this era of instant gratification was the diet pill Dexatrim. Released in 1976, these pills were actually formulated by S. Daniel Abraham, the creator of the Slim-Fast drinks. The pills were advised to be taken daily as an appetite suppressant and sold over-the-counter, but they also had scary side effects, including increasing the risk of stroke. The advertisements of the age were extremely unsettling and emphasized women’s insecurities while marketing directly to them. Also, people didn’t want to have to change their lifestyles to accommodate this idea of austerity or cutting back. If a product existed that was easy to consume, and promoted by industry experts, then why not try it.

I completely understand why Cathy had crippling self-doubt: she was just trying to cope with the world around her, which is probably why she was so beloved by boomer women. Sure, Cathy made poor choices like buying too many clothes and indulging in crash diets or complaining why something that was supposed to magically work didn’t, but could you blame her? As a call-back to the self-serving ethos of the “Human Potential” movement, Cathy was always focused on becoming the most optimized version of herself, no matter the cost. The ultimate specimen to be sold the promise of big, life-changing products.

Just two years after Cathy in 1976, and in the middle of this supposed “narcissism epidemic” an orange cat debuts in a comic strip in Indiana.

Jim Davis created Garfield out of “a conscious effort to come up with a good, marketable character.” At his core, Garfield the cat and the strip itself are the product of a consumer-driven culture. The cynical orange cat is based on an older male family member of Davis, who hates Mondays and loves lasagna and all sorts of food. While Garfield’s smug attitude and passive-aggressive comments about his family may seem laughable and innocuous, this orange cat spoke to a generation.

Every time Garfield bemoans Mondays it’s a visceral feeling; It’s the day when we muster up the mental strength to sit at our little desks with terrible posture, toiling away for hours in a banal office somewhere, attempting to pay the rent, put food on the table, and live comfortable albeit monotonous lives. Even Garfield’s occasional comments about going on a diet himself, it is utterly representative of the consumer mentality: the cycle of self-defeat buoyed by the purchase of a new outfit or the latest diet fad. While Garfield may not have direct experience outside the home, he represented, this disdain for what society has become while at the same time living out those same tropes himself.

What both Cathy, Garfield, and the pop culture of the late 1970s show us, is that a society is ultimately not a communal, selfless utopia, but rather a mass of cynical, self-involved individualists anxious about the future. Capitalism rules, and we’re all along for the ride.

The late seventies in America represented a new age of consumerism— an age dictated by quick fixes and a burgeoning mall culture. By 1975, shopping centers accounted for 33% of all retail sales in America. Victor Gruen, the architect credited with creating the shopping mall, hope to achieve a cosmopolitan allure while also establishing a place where people could gather and share ideas. The genesis of the shopping mall was drawn in the spirit of utopianism, akin to the Human Potential Movement and the communes of the early 1970s.

Yet much like the crushing reality of the late seventies, developers often cut costs and focused on ease of use by surrounding malls with giant parking lots, housing projects, and car dealerships. Instead of leaving one’s individual home to join a community of ideas and intellectuals, the mall became just another place to buy stuff.

The mall is a major theme in the Cathy comics. Cathy is often seen in the strip trying on a swimsuit in a dressing room with high hopes that she will look thinner, richer, or better than she imagined. Of course, the joke is that she’s almost always disappointed by the reality. This disillusionment with reality is a theme that runs through a lot of media in the late 1970s and into the early 1980s, with malls often as a backdrop. In George Romero’s horror classic, Dawn of the Dead (1978), humanity’s last stand against an army of zombies actually takes place at a Pennsylvania shopping mall, with a group of well-meaning individuals getting picked off one by one. In its climactic scene, Romero captures the eventual invasion of zombies bashing through a mid-tier department store, quite literally to say that modern society has become a pack of self-serving, consumer zombies. It’s fitting that just one year later, in 1979, Jimmy Carter would address the nation again with the same critique of American culture with a preacher-like zeal

“In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities and our faith in God, too many of us now worship self-indulgence and consumption.”

People didn’t want to hear this negative attitude and displeasure with modern life in the late 1970s, but they were ready and willing to soak in the self-deprecation and cynicism from the comic strips of Garfield and Cathy.

At a certain point, it’s predictable that the progressive pendulum of the early 1970s would swing back the other way. The harsh reality of structural change is that it can take decades. This is probably why a progressive like Jimmy Carter lost so badly to Ronald Reagan in the 1980 election - people wanted change in an instant-gratification world.

Garfield was better at speaking to the masses than Jimmy Carter, but maybe he was more in touch with how people really felt. Modern life in the 1970s could be soul-crushing, and to an extent, it still is.

For Further Enjoyment-

Top Tracks:

NYT Article from November 30th, 1977 - Narcissism in the 'Me Decade'

Cathy Guisewite on Johnny Carson

B-Sides:

Jimmy Carter's Malaise Speech (1979)

Garfield in The Fantastic Funnies (1980) First Animated Appearance

Enjoyed the cartoon journey. Cartoonists have long been able to get away with social commentary that otherwise would not have appeared in print. You would look at them with a wry smile, knowing the message was often on point.