With election season upon us, it’s the perfect time to dive into some of the zaniest, and downright shocking political scandals from the 1970s. Much like the cacophonous rhetoric from the Donald Trump era, or the sexual exploits of Bill Clinton, the 1970s were equally as chaotic. It was the era when tabloid-style sensationalism came of age, and leached into mainstream culture. Whether it was politicians or celebrities, indiscretions of the rich and famous were feverishly written about in the press and consumed by the masses.

With the amount of surveillance and spectacle, you’d think those in power would tamp down unseemly behavior, and maintain some privacy. Yet from the most prestigious in society to the lowest on the fame scale - it turns out that people are bold, brash, and let their egos take charge. When it comes to celebrities in the 1970s (and especially today), people want to express themselves, out loud, and if possible… in front of an audience.

The 1970s are often referred to as The “Me” Decade, due to the perceived self-indulgence of the baby-boomer generation and the expansion of alternative lifestyles. People experimented and began taking risks when it came to their image and way of life. While this new environment of social and moral ambiguity gave people motivation to act on their instincts, it also lead to bad behavior. And when that impulsivity went a little too far, especially in the world of politics, the culture was watching, waiting, and ravenous for the dirty details.

When we think of political scandals and the 1970s, the first thing that comes to mind is Watergate. Even 50 years later, this scandal truly changed the landscape of institutional trust in this country. I will most likely cover Watergate its own dedicated chapter of Boogie Shoes, but below is a quick summary:

The 1972 Nixon re-election campaign conspired with a few individuals close to the President to break into the Democratic Party’s headquarters in the Watergate Office Complex in Washington D.C. The plan was to steal documents and install listening devices in telephones to gain an edge on the competition for the election. President Nixon knew about all of this and paid the burglars before the break-in occurred.

Through the reporting of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein at the Washington Post and their source Mark Felt (aka Deep Throat), it is revealed that The President knew about the burglary, and attempted to cover up the White House’s involvement. President Nixon secretly recorded meetings in The Oval Office, where him and staff brainstormed with aids how to cover up the Watergate break-in. These are released to the public, and soon after President Richard Nixon makes an address to the American public from the Oval Office on August 8, 1974, to resign.

Nixon’s involvement in the scandal is a flashpoint in American culture, and a reminder of the sheer hubris of a man with political power. Several historians and media experts point to Watergate as a catalyst for the U.S. population’s collective cynicism towards government institutions— I tend to agree.

The feelings of distrust across society remained through the Ford Administration and beyond. Average citizens were upset. They were suspicious of all authority figures, and those seeking answers even entertained the idea of conspiracy theories and extreme ideology. This new climate of distrust seeped into the media landscape in everything from print publications to major motion pictures. From political thrillers like All The President’s Men (1976) or The Conversation (1974) to 1977’s media drama Network, negative attitudes towards institutions were pervasive in popular culture. Pair this anger with evolving standards of acceptable behavior, and average citizens assumed the role of judge and jury for the powers that be.

Beginning in the 1960s, tabloid magazines began to show up in supermarket check-out aisles. Circulation grew throughout the 1970s, with shameless headlines catching the eye of shoppers as they waited to scan their groceries. It was hard to pass up a juicy story like “Ford’s Flirtations with Hollywood Beauties…” The Globe, and The National Enquirer were weekly publications that reported on salacious celebrity stories, but in 1974, Star Magazine debuted, and tabloids began their epic rise. While not overtly political, gossip magazines became a bridge between the world of celebrity and political scandal. The Kennedys, Nixon, and several other political figures appeared on the pages of these supermarket specials, and some still do even in 2022! Most notably, in the mid-1970s Carol Burnett actually sued The National Enquirer after it reported on a drunken encounter between her and Nixon Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Celebrities became less tabloid-friendly as a result, but that didn’t stop readers or publishers from capturing mean-spirited, cynical tales of people in power behaving badly.

In a newly democratized and flourishing magazine industry, it was more difficult for politicians to sweep unflattering stories under the rug. Readers were going to voraciously consume these stories, ready to be entertained by the lowest-common-denominator. One such scandal that fits neatly into this box was a sexual tryst between exotic dancer Fanne Foxe and Democratic Congressman Wilbur Mills. Mills was the Congressional Chairman of the Ways and Means committee, and Foxe was a performer at the D.C. club The Silver Slipper. At the time, Wilbur was introduced to Fanne through a mutual friend and fellow performer at the club. The two grew close and developed a relationship, even though both were married. Wilbur Mills even moved, with his wife, into the same apartment building as Fanne Foxe and her husband, and the couples would play bridge together! Talk about a very groovy, 1970s-style open arrangement.

In Foxe’s memoir, she wrote that Mills had promised to marry her if he could get a divorce. Foxe also stated that she was pregnant with Mills's child at one point, but got an abortion to protect his reputation. Knowledge of their affair in Washington D.C. was fairly well-known, and while Foxe was no longer performing, she and Wilbur Mills were seeing each other and going to clubs. One night, in the summer of 1974, after getting into a drunken argument at The Silver Slipper, Foxe and Mills were driving home near the Jefferson Memorial and were pulled over by the Park Police. Foxe panicked, ran out of the car screaming, and attempted to flee the scene by jumping into the Tidal Basin, but the police pulled her out and handcuffed her.

The event was all over the media and D.C. press, and Wilbur Mills was in the middle of a congressional election. He narrowly won his seat, and Fanne Foxe had so much publicity that she started performing again as the “Tidal Basin Bombshell.” What’s even messier about this whole thing is that Wilbur Mills continued to make their relationship work and didn’t want her dancing. Shortly after winning his seat, Mills showed up at a club in Boston where Foxe was performing and drunkenly demanded she gets off the stage. The nerve! It makes me happy that Fanne Foxe lead a very long, normal life after this entire episode because she was just doing what needed to. Mills resigned in December 1974, and I’m not really sure what happened to him after that.

The theme of men in power behaving badly during the 1970s is strong from the beginning of the decade through the end. What kicked off the 1970s, and one might argue is one of the biggest moments in political scandals of the 20th century, is what happened at Chappaquiddick in 1969 with Ted Kennedy.

The Kennedy family has always been about legacy. The family has dominated the political and media landscape of The United States for generations. While tragically President John Kennedy and his brother Robert Kennedy were assassinated in 1963 and 1986, respectively, the rest of the family has been no stranger spectacle in the years since. Edward “Ted” Kennedy was the youngest of nine siblings in the Kennedy family and had grandiose political ambitions like his brothers and father.

In 1969, Ted Kennedy was the current senator of Massachusetts and was looking to the future after working on Robert Kennedy’s tragic presidential campaign. He held a party in the Chappaquiddick Island area of Martha’s Vineyard for some of the women who worked on Robert’s campaign. He left the party with 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne and was clearly intoxicated. Ted Kennedy tried to cross the Dike Bridge while driving them home, and lost control, crashing into a body of water. Kennedy escaped from the overturned vehicle, and, unsuccessfully attempted to save Kopechne. Ultimately, he swam to shore and left the scene. Kennedy did not contact police until the next morning, by which time Kopechne's body had been discovered by locals.

A week after, Ted Kennedy pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident and served two months in prison. This was a major national story and Kennedy attempted to “save face” by apologizing, deflecting, and claiming that he was not under the influence of alcohol, and also claimed that, as a married man, he was not doing anything immoral with Mary Jo Kopechne. Kennedy’s work to save his image and express guilt allowed him to remain in office as a senator and he even ran for president in 1980. In HBO’s prestige drama Succession, heir-apparent to the Roy Media Dynasty, Kendall Roy, has his own version of a Chappaquiddick incident. He also doesn’t report an intoxicated car accident to the police, accidentally killing a waiter he’s befriended while doing drugs, and endures fallout from the press and political establishment. While Kennedy remained a popular figure in politics until his death, it shined a light on the power of the Kennedy Dynasty and corruption.

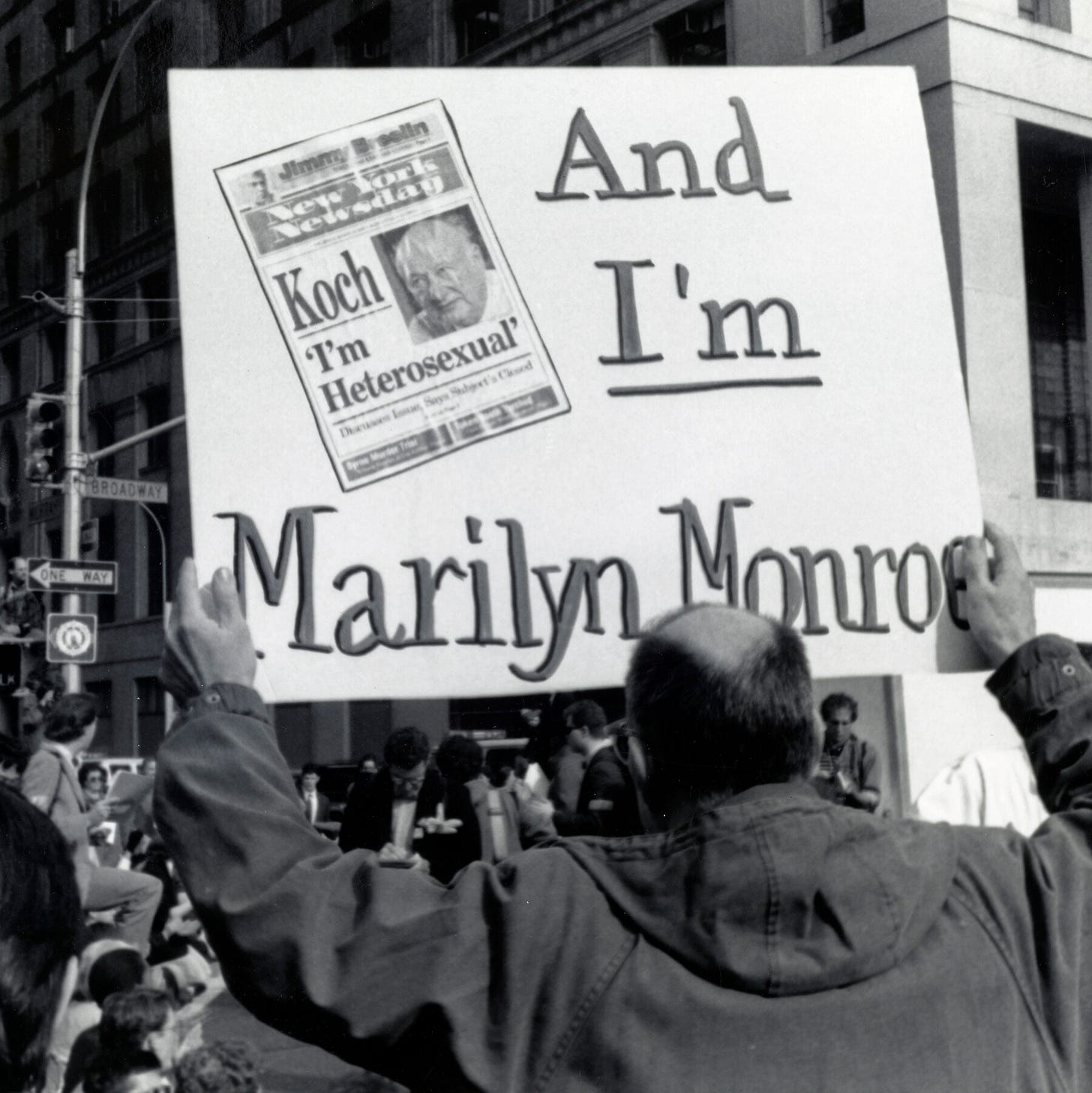

In the late 1970s, a beloved New York politician had his own salacious episode, but for very different reasons. Mayor Koch began his political career as a pioneering ally of the LGBTQ+ community. He was one of the first politicians to be a vocal supporter of gay rights on the national level and courted the lesbian and gay electorate in his winning 1977 mayoral campaign. In 1974, Koch was also one of the initial co-sponsors of the federal gay and lesbian rights bill in Congress, along with his Manhattan Democratic colleague Bella Abzug.

Yet, as soon as Koch became mayor, all of this support and goodwill vanished. He inefficiently responded to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s by ignoring the calls to declare the pandemic a public health emergency. During this time, Ed Koch cozied up to high-end real estate developers and embraced the city’s elite with tax breaks and neo-liberal policies, with some accusing him of abandoning those marginalized groups that fought for his election. The economic impacts of new luxury buildings in notably LGBTQ+-friendly neighborhoods further exacerbated New Yorkers who were not only in the middle of a pandemic but also reeling from the impacts of gentrification.

This all sounds like a straightforward case of a lapsed progressive politician giving up their morals, but what made the case of Ed Koch so irritating for his entire career, and a fixture in the tabloids, was his secret life as a gay man. In interviews, he countlessly claimed he was heterosexual, but that was not the case. According to several former partners, sexual partners, and members of his inner circle, Ed Koch was part of the same LGBTQ+ community he abandoned during this mayoral career. Koch’s reluctance to claim his identity felt like a gut punch. Because his sexuality was an open secret, it created even more resentment, especially when he refused to address the AIDS crisis. Mayor Koch waited until 1988 to take any real action against the pandemic.

If you’re at all politically engaged, you’ve probably received an email in your inbox from one of the parties, interest group, or a Political Action Committee (PAC). What I find hilarious about these emails, is how often the messaging reads like it’s from a tabloid. The content is feverish; ruthless accusations against the opposition, countless absolutisms in 300 words or less for a 3rd-grade reading level. Whether it’s political fundraising, or better yet the tabloids, or reality television for that matter, this distrust of the establishment digs at our primal urges, and clearly thrives in times of chaos (like the 1970s). Whether it’s Watergate, or Wilbur Mills, or even Jimmy Carter’s aid snorting cocaine at Studio 54, all of these scandals played out in public view, feeding our nature to simplistically view the world in absolute terms.

The 1970s era of scandal and tabloids clearly lives on today, because the drama of personal woes mixing with professional ones are fascinating. It’s the reason why year after year, nothing captures the collective attention in an election like a political scandal— and it’s why our media culture has become one big supermarket tabloid.

For Further Enjoyment-

Top Tracks:

The Saturday Night Live Episode That Changed American Politics

Succession: The Real-Life Tragedy That Inspired the Finale’s Twist

B-Sides:

Former New York Mayor Ed Koch Remembered in Pop Culture

Geraldo: Season: 2, #13, January 23rd 1975 - Fanne Foxe Interview